Key Learning Points: The Innovator’s Dilemma is the title of an excellent book by Clayton Christensen. The dilemma itself is the fact that though large innovators have some motivation to innovate, they also have a strong disincentive from doing so as new products will undermine their existing ones.

The Innovator’s Dilemma

The innovator’s dilemma is very really problem that organizations face on a daily basis. They know that to survive into the future that they need to be producing the products of the future, and this means they need to be innovating. At the same time though, they also know that if they create a new product that they’ll be disrupting their existing, profitable products.

In our consideration of the innovator’s dilemma, we really focus on one aspect of this work, which is the concept of “S-curves” of innovation.

Innovation S-Curves

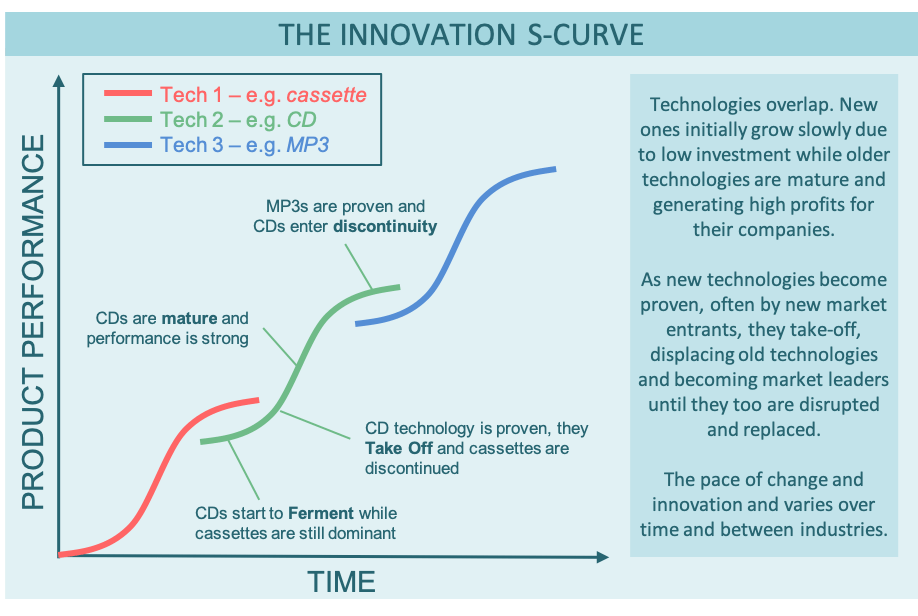

So what is the innovation S-curve? Well, it is a model capturing a product or technology’s life-cycle. The model effectively tracks the impact or popularity of a technology or product from the point at which it’s first conceived of, to the point at which it is retired.

There are four stages in this model: ferment, take-off, maturity and discontinuity. The model plots performance (typically sales) vertically against time horizontally. The model says that the relationship between these dimensions for a product or technology adopts an “S” type shape. The gradient of this S curve shows how rapidly the new product or technology is being adopted (or dropped) by the market.

A particularly interesting feature of this model is how it effectively shows the transition between dominant technologies over a period of time. Each technology goes through one S in its lifetime. At the early stages of its life, it is competing with the technology that preceded it. At the later stages of its life it is competing against the technology that will ultimately replace it.

To help bring the S-curve to life, we’ll consider these stages below, with a focus on CDs as a technology.

At first, new technologies forment

And lo, before there were CDs there were cassettes. At the start of the technological life cycle of CDs, cassettes were the dominant technology in this domain. Their S-curve had a steep gradient. When CDs are introduced their curve has a shallow gradient. They don’t make rapid inroads into the market, they simply ferment along as they attract early adopters and start to be accepted by the market.

At this stage they have some impact on the market dominance of cassettes, but not much. The cassette is king.

Once established, new technologies take off

After a while though, the early adopters have tested the CDs and found them to be good. They promote them, marketers promote them, production volumes increase a bit, production costs fall a bit and the new technology finds a place in the world.

The curve steepens and the impact on the market is more pronounced. Mainstream consumers start to substitute their old cassette buying habits for new (and literally shiny) CDs.

At this stage new technologies really start to take off. Unfortunately though for the cassette, the rise of CDs signs the decline and discontinuity of the once mighty cassette tape.

After take off, technologies mature

CDs are flying off the shelves now. Even late adopters know that they are the go-to technology for audio media. Everyone is buying them. Their increased sales volumes have hugely boosted production numbers. These scales of production, combined with incremental innovations have greatly reduced their costs as well.

The once new CD has fully arrived. It’s loved by its consumers who consider it good value, and by its producers who generate great profits from it. The cassette is dead, long live the CD, the new mature technology in the market.

But unbeknownst to the CD, there are new stirrings in the market place. A few people have been asking if your even need CDs any more, or if you can just have hard-drives with audio files. These people are experimenting with MP3 players, and some early adopters are taking notice of this new technology that’s beginning to ferment.

After maturity comes discontinuity

The mighty CD now starts its inevitable decline. Its curve becomes more shallow. It’s sales volumes fall. The incremental cost of production of each CD increases marginally as volumes decline. Organizations move their capital away from CD production towards new ventures to generate higher returns on equity. A few die-hard stragglers continue to buy CDs, but even they are starting to lose interest. Production splutters on for a while until it ultimately discontinues.

Of course, one technologies demise is another’s rise, and it is now the time of the MP3 player.

However, as with all technologies, it too will be replaced. It’s not long after the birth of the MP3 that people start asking why we need to own our music and why we can’t just stream it.

And so the cycle repeats

The S-curve tracks the rise and fall of technologies over time. Of course, not all make it through all the stages. Many ferment but never take off, but the dominant ones follow this trend. And it’s this trend that causes some problems for innovators.

After all, if you were a dominant market player profiting well from a mature product, would you want to innovate a new replacement for it?

The dilemma

So there is a clear dilemma. While market players who are not in dominant positions have a clear incentive to innovate, so that they can gain entry into a market, market leaders have no such incentive.

In fact, market leaders have a disincentive. All those producers who’d invested capital in CD production capability and were profiting well from their investments want nothing less than to see a new technology come to the market place.

At the same time though, they know that if they don’t innovate themselves, someone else will and they may well lose their place in the market all together. Blockbuster, Kodak and other vanished entities are reminders of the perils of failing to move with the times.

So what do they do? Should they invest in innovation and risk undermining their own market leading products in an effort to stay ahead of the curve? Or should they focus their resources solely on their market leading products? This is the question leaders must ask themselves every day when shaping their product portfolios and investment strategies.

Luckily for them, there are more options that just the two outlined above.

And the responses

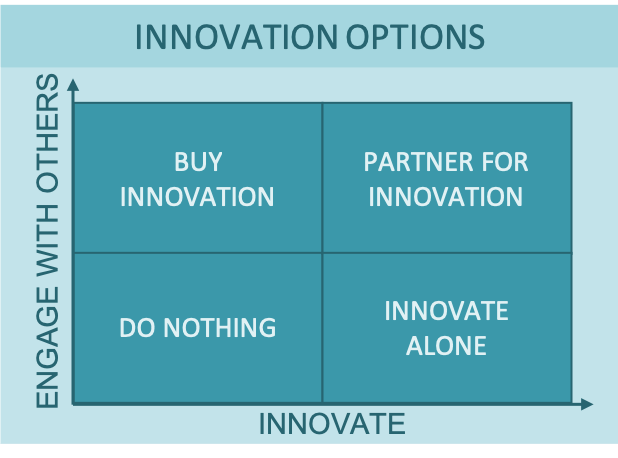

Organizations have a range of options that they can undertake in relation to innovation. We like to consider their options to be broadly speaking scalar between two dimensions: how much they engage with others, and how much they contribute to innovation themselves.

This structure leads to four broad strategies relating to innovation. Of course, organizations can adopt a mix of strategies across a mix of products or times. Despite this, we think this framework is a useful way to conceptualize some strategic decision making criteria.

Option 1: Don’t engage with others, and don’t innovate internally

This is the “do nothing” option. Here organizations choose not to invest in innovation internally. They also choose not to engage with others in relation to innovation.

In some industries, where product life-cycles are particularly long, or where product differentiation or marketing positions mean consumers are particularly loyal, this may be the right strategy. While Coke has innovated with new products and processes, it proudly states that its core product has retained its “original taste since 1886”.

Option 2: Invest in innovation, but don’t engage others

This is the innovate alone option. Here organizations potentially become specialists in innovation, grow large research and development teams and become silos of creativity and product development.

This may be beneficial in industries where existing products have limited life-cycles and rewards are high, or where there are complexities associated with working with others. An example of where this strategy may work is in the pharmaceutical industry.

Option 3: Don’t invest in innovation internally, but engage a lot with others

This is the buy innovation model. Here large organizations may know that their strengths lie in operational effectiveness and bringing products to market, but not product development. Instead of investing their capital in developing products, they instead trust themselves to pick winners, buy products, bring them to market and deliver them efficiently enough to generate suitable returns on capital.

Increasingly, some players in the tech industry can be seen shifting more towards acquisition of companies and innovations (as well as of innovative teams).

Option 4: Invest in your own innovation, and engage with others

This is the partner for innovation model. Here organizations invest in and shape the innovative process, but know that they don’t have the capability to innovate alone (or see other benefits in collaboration) so they work with other partner organizations on innovation.

This strategy has been popular recently in the FinTech space where traditional banks partner with newer, more agile and technologically capable partners for combined product innovations.

So what’s the right answer?

Well, as ever, there isn’t one. Ever situation is a bit different, and every organization brings its own strengths, weaknesses, strategy, stakeholders and vision with it to the decision making process. While there is no one right answer, there are many options to choose from.

Learning More

It’s worth thinking about the difference between initial and incremental innovation. It might also be worth reading more about the Medici Effect, which considers the benefits of diversity on innovation. We’ve written a little on cultures and leadership for innovation and discussed the hackathon tool, as well as problem solving.

Our View

The innovator’s dilemma is an interesting one. That said, we think that as the pace of the world increases, it’s increasingly clear that organizations need to innovate quickly. Of course there are exceptions to this rule, like the example of coca-cola which we touched on earlier.

Organizations like Coke can defend a market position through marketing and the use of intellectual property laws, but this might not always be the case.

We particularly like the S-curve approach to tracking and understanding the rise and fall of technologies, and think it’s a good way to communicate how innovation affects products.

Overall we think that most people will benefit from knowing about this concept more theoretically than they will practically, but it’s still a good think to understand and be aware of.

How We Help Organizations

We provide leadership development programmes and consulting services to clients around the world to help them become high performing organizations that are great places to work. We receive great feedback, build meaningful and lasting relationships and provide reduced cost services where price is a barrier.

Learning more about who we are and what we do it easy: To hear from us, please join our mailing list. To ask about how we can help you or your organization, please contact us. To explore topics we care about, listen to our podcast. To attend a free seminar, please check out our eventbrite page.

We’re also considering creating a community for people interested in improving the world of work. If you’d like to be part of it, please contact us.

Sources and Feedback

Christensen, Clayton M. The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 1997.

We’re a small organization who know we make mistakes and want to improve them. Please contact us with any feedback you have on this post. We’ll usually reply within 72 hours.