A cognitive bias is a persistent, biased pattern of thinking or decision making. These biases usually cause people to reach “incorrect” or irrational decisions. There are many different specific cognitive biases (more than 200 and counting). Though their results are often “irrationality”, in some circumstances they may actually be helpful.

Summary by The World of Work Project

Cognitive Biases

A bias is a prejudice (a pre-judgement) in favor of something and cognition broadly means thinking. This means that that a cognitive bias is basically thinking in such a way that you pre-judge things as opposed to rationally analyzing them.

One common place where cognitive biases are often seen to appear in the workplace is in relation to recruitment. Most people make irrational hiring decisions based on a range of cognitive biases.

Many people consider cognitive biases to be sub-dividable into different groups of biases. For our purposes we use three different categories of biases:

You can see examples and read more about each of these bias types in the separate posts we’ve created.

How do Cognitive Biases Work?

Basically what happens with a cognitive bias is that we make decisions or assess situations using shortcuts. These short-cuts, rules of thumb or gut feelings are often referred to as heuristics. They help us reach decisions quickly, but these decisions are not always strictly speaking rational. The ways that we are biased when it comes to making decisions are many and varied. They include, but are not limited to:

- Ignoring important information,

- Treating irrelevant factors as important,

- Incorrectly weighting information,

- Finding false correlations,

- Creating false memories as a basis for decision making,

- Being swayed by social groups and pressures, and

- Miss-assessing the desirability of outcomes.

You can explore more about the difference between more effortful, rational thought and less effortful heuristic based or otherwise biased thought in our post on Dual Process Theory.

Why are Cognitive Biases Important?

It’s important to understand cognitive biases for several reasons. From an individual’s perspective, it’s helpful to become aware of our own cognitive biases so that we can seek to make more rational decisions (if we decide that rationality leads to better outcomes).

From a leadership or organizational perspective it’s important to understand cognitive biases. It is these biases, in part, which help explain how individuals think and feel on a day to day basis. And it’s how they think and feel that shapes their overall performance and engagement in our teams and organizations.

An important thing to bear in mind about cognitive biases is that everyone has them. All of us do, even those of up who really think we’re rational. And we all have different blends of them. In short, the way we think about and decide on things as a species is gloriously irrational. But it is irrational somewhat predictable way. If we explore this line of thinking further we may start to question what reality is and whether individuals create their own realities. See some of Anil Seth’s great work on the neuroscience of consciousness for more on this.

Of course, whether or not rationality really desirable is a whole different question. But it’s beyond our ability to fathom so we won’t try to address it.

Some Cognitive Biases to Consider

Many cognitive biases have been discovered since the mid 20th century, when they really started being systematically collated. You can read about them in many places on the internet. We’ve created several different posts on them, each looking at a different bias or grouping of biases.

We’ve tried to focus on biases that we think are relevant for the world of work. Again, you can access these thematic bias pages through the following links:

We’ve also provided more details on three specific biases in this post to help bring the concept to light.

The Mere Exposure Effect (decision bias)

The mere exposure effect is a cognitive bias which says that the more someone is exposed to something, the more positively they will be disposed towards it. In other words, familiarity breeds favorability.

This phenomenon has been proven to be true in a wide range of studies. It’s existence forms the basis of the effectiveness of things like brand-awareness based advertising. As they say, “there’s no such thing as bad publicity”.

In a work perspective, this cognitive bias can play a variety of roles beyond that of public advertisement. For example, internal communications teams can take advantage of this bias by consistently repeating the same messages and graphics in relation to a future strategy. In doing so, they will usually increase overall employee positivity towards the strategy. Similarly, leaders can increase their presence and visibility with their teams. Again, this exposure will most likely increase the positivity with which the leader is seen by the team.

The Halo / Horns Effect (social cognitive bias)

The halo effect is the name given to a cognitive bias we have which means that if we consider someone to be good at one thing, then we also consider them to be good at other, unrelated things. This is often true even if we have no evidence of that being the case.

For example, if you meet someone and discover that they are great at tennis, then you will subconsciously increase your internal assessment of their ability at totally unrelated things like public speaking, geometry or knitting.

In other words, where people have a strong skill in one area, we consider this an indication of a wider, encompassing greatness in all areas of life.

This effect doesn’t just work in a positive light though. The horns effect is the name given to the inverse of this bias. The horns effect is the phenomenon whereby if we know someone is bad at one specific thing, we assume they will be bad at wholly unrelated things as well.

The halo and horns effects clearly have a very important role to play in the workplace. They can significantly shape our assessment of those around us. They are particularly important in areas like performance management and group calibration. It’s hard to let go of biases and to assess people objectively, but it’s important to try to do so.

The Zeigarnik Effect (memory cognitive bias)

The Zeigarnik effect is the name given to the fact that we remember things that have failed to be completed or which have been partially completed much more than things that have been completed.

For example, if you fail to complete one monthly report, but successfully complete the other nine that you are responsible for, you will remember the one and forget about the other nine. Unfortunately, most of the others with whom you work will also only remember the one thing that went uncompleted.

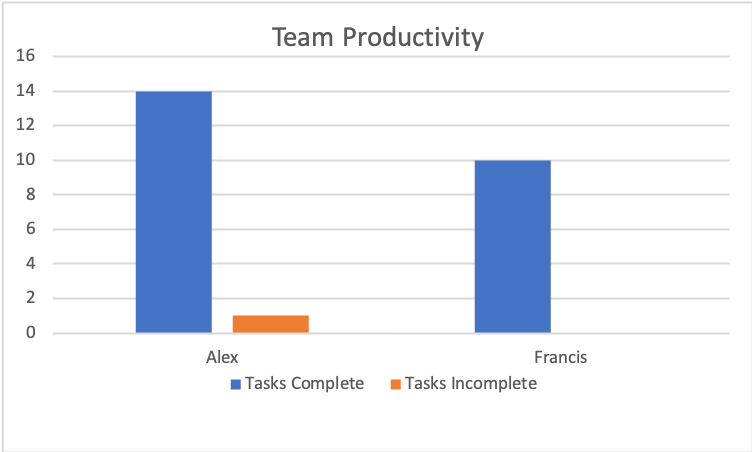

From a work perspective, this means that the things we do not complete carry much more weight with others than the things that we do complete. If you complete 14 tasks and fail to deliver one task, and one of your peers only completes 10 tasks but fails at none, then chances are that your peer will be more well thought of than you. The others around you will not remember that you actually completed 40% more tasks than your peer, but they will remember that you failed to deliver something, where your peer did not. Obviously this is fairly ludicrous, but it’s the way we think. So with this in mind, never over-commit!

Learning More

The way we think as humans is fascinating. Cognitive biases clearly explain some of our “irrationality”. Understanding our Dual Process way of thinking provides some further insight into it. This “irrationality” means that we’re all suggestible and susceptible to nudging and the powers of choice architecture and persuasion.

Communication is another tool often used to change people’s behaviors. Ideas like the rhetorical triangle and the five canons of rhetoric shed some light on how this works. For a more detailed look at communicating for persuasion, explore Monroe’s Motivated Sequence.

Increasingly, products are also design to be persuasive, as it were. They are designed to create habits and drive increased use. Examples of this include Fogg’s model and the Hook model of behavioral design.

You can listen to our podcast on congnitive biases and sustainability below:

The World of Work Project View

We think that cognitive biases are fascinating, and we like the irony of the fact that we are biased in believing that others are more affected by cognitive biases than we ourselves are.

Cognitive biases certainly do lead us to make irrational decisions on a predictable and consistent basis. While in some instances this is clearly a negative thing and results in negative outcomes for ourselves and those around us, there are some instances where we’re not sure that behaving “rationally” is really the best thing to do. If our overall goal in life in general wellbeing and life satisfaction, then perhaps we’ve collectively ascribed too much importance to the role that “rationality” plays in helping us achieve that goal.

What we’re really getting at with this is that we believe that our definitions and calculations of rationality aren’t necessarily good enough or complete enough to be very useful in the real world. Thus the death of homo economicus.

Despite some of our doubts about the merit of rationality, we think that understanding the concept and specifics of cognitive biases is helpful for individuals and leaders in the world of work.

How We Help Organizations

We provide leadership development programmes and consulting services to clients around the world to help them become high performing organizations that are great places to work. We receive great feedback, build meaningful and lasting relationships and provide reduced cost services where price is a barrier.

Learning more about who we are and what we do it easy: To hear from us, please join our mailing list. To ask about how we can help you or your organization, please contact us. To explore topics we care about, listen to our podcast. To attend a free seminar, please check out our eventbrite page.

We’re also considering creating a community for people interested in improving the world of work. If you’d like to be part of it, please contact us.

Sources and Feedback

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Ariely, Dan. Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions. New York : Harper, 2009. Print.

We’re a small organization who know we make mistakes and want to improve them. Please contact us with any feedback you have on this post. We’ll usually reply within 72 hours.